Home Page Books Overview Page

How to Write a Novel in One (Not-so-easy) LessonJackie shares her knowledge of the craft of writing in this short but jam-packed book. It draws on her experience in teaching more than 100 students. Kindle or Nook, Kobo or Apple, or on Smashwords (multiple formats)

|

Welcome to Jackie's blogs!

Mistakes to Avoid in Your Writing Career

Tips for Writing Funny Fiction

Mistakes to Avoid in Your Writing Career

Part

1: The Journey to Publication

Attitude

issues:

Don’t

dump on yourself or let anyone else do so. In my teaching, I was shocked

by how many students took negativity from parents, spouses, so-called

friends. Sometimes it’s disguised as helping: “I don’t want you to be

disappointed.” They should support you or get out of your way.

If

they won’t, make new friends. I won’t advise you to get a new husband or

wife, but the one thing that’s vital to any successful relationship is respect.

Dumping on your dreams is disrespectful.

Don’t

let fear get in your way. Fear of writing,

fear of failing, fear of rejection, fear of criticism. Every time I start a

book, I’m afraid I’m going to fail. And that’s after nearly 100 of

them. I have had books come up short—some that didn’t sell, some

that required major revisions, some I set aside and never finished.

You

will never move from Point A to Point Z or even to B if you listen to your

fears. Just accept that failure is part of the process.

Remember

that, once you succeed, your failures are just interesting stories for you

to tell.

Some

rejections or critiques are really cruel. That doesn’t make them

right. Some people are just mean. And the fact that they may hold positions

of power doesn’t necessarily mean they’re right, either. I once had an

editor at Harlequin—before I sold to them—who told me I wasn’t cut out

to write romance.

Sometimes

a rejection or criticism will strike you as accurate. Don’t let that

devastate you. You screwed up. Ouch! After you pick yourself up, take

what’s helpful and don’t give in to the sense that you’re a failure.

Mistakes don’t mean you can’t become a good writer.

Don’t

think that failure means you’ll always fail. As

a writing teacher I have seen students start out at a level where they could

easily be dismissed—voice all over the place, no idea how to use point of

view, etc. But they worked incredibly hard. Amazingly, after a year or so,

their writing reached a professional level.

Don’t

let anyone browbeat you, and this goes double

if they aren’t in the writing/publishing field. The most ignorant

people—including those who know nothing about publishing—can be among

the most overbearing about how right they are in whatever nonsense they’re

spouting. For example: “Everybody knows that sex sells, so you should

write that!” Only if you feel comfortable with writing sex.

Don’t

feel you have to write everything. Just

because erotica is selling, if you can’t bear to read it, don’t try to

write it. The same goes for any other trend or type of fiction.

Don’t

be afraid to try something new. Don’t limit

yourself at the beginning of your career or in the middle of it, either.

It’s wonderful to have a particular brand if that’s fulfilling for you,

but if you’re dying to try something else—or if you’re facing

burnout-- go for it.

Don’t

rush. Just

because you hear that you should leap into submitting or self-publishing

while the iron is hot—don’t do it if the manuscript is still rough, or

your skills aren’t ready for prime time. You may lose

readers—permanently. And oh, those online reviews can be cruel.

Learn

to say no

to people who infringe on your writing time. You may lose friends. You will

make new ones. Don’t say “I’m trying to write” or even “I’m

writing.” Say, “I’m working.”

Part

I

Bottom

line: Never forget that your reader wants to go on an emotional journey

with your characters, to care about them, to get involved with them, and to

feel satisfied at the end. If

you don’t accomplish that, nothing else matters.

Don’t

shy away from emotions. In my experience, most people read novels,

especially romance novels, for the emotional experience.

Make

sure there’s something absolutely vital at stake for your

characters. If a pretty young woman goes to a dance and meets a nice guy but

has to leave early, so what? Think about all the reasons why Cinderella’s

prince actually matters.

Don’t

assume that you can write a novel the way you see things in movies or on TV,

mostly through dialogue and action. You don’t have actors and a director

to focus in on the emotions.

That’s

where point of view comes in. Point of view is the primary

tool by which the author involves the reader emotionally with the character

or characters. It means filtering events and perceptions through a

character.

Watch

out for head-hopping.

This means jumping back and forth in viewpoint like

a pingpong match.He says something and he thinks something. Then she

says something and she thinks something. It keeps the book at a shallow

level, and discourages strong identification with a character.

Don’t

write “in general”—generic plot,

characters, etc. Avoid treating your characters like characters--treat them

like people. Make sure their actions are motivated.

Never

say, She was average height, or he resembled a typical bodybuilder. That’s

generic thinking. Not every hero has to have a sculpted chest and not every

heroine has to be the most beautiful woman he’s ever seen. That isn’t

what makes us fall in love. If it were, more movie stars would have happy

marriages.

Clip

out photographs if that helps you be specific. But avoid citing a movie

star, as in “he looked just like Brad Pitt.” What if your reader hates

Brad Pitt? Or what if Brad Pitt does something shocking by the time the

reader reaches that description? Also, to me, it sounds lazy.

Don’t

write generic crowd scenes. To bring a crowd

scene to life, pick out a few specifics. Describe one or two individuals and

let the reader see them in a little detail.

In

description, don’t provide a laundry list. Don’t mention every feature

of a room; pick a few salient features. The hero or heroine’s house or

office should reflect that individual’s personality and background.

Don’t waste description—use it to provide insight. Is there a piece of

memorabilia she acquired while living in India? How about a photo of his

dead wife?

Also

avoid recounting every move the character makes. In rereading your work, if

you can take something out without losing clarity, do it.

Use

your senses, and be specific. Instead of

saying “nostalgic odors,” say the scent of gingerbread baking at

Christmas.

Make

sure you can visualize the setting. I draw maps and floor plans for houses

and other buildings, such as my Safe Harbor Medical Center.

Don’t

waste the reader’s time. Avoid chitchat and busywork. The

hi-how-are-you kind of conversation has no place in fiction. If it doesn’t

have emotional content or it isn’t funny or interesting, skip it. Dialogue

should always reflect character.

Push

your characters outside their and your comfort zones.

If you play it safe—you will lose your reader. You and I probably lead

boring lives, and like it that way. Our characters should be larger than

life. They can have emotional meltdowns that would embarrass our socks off.

Don’t

make every person into yourself. What your

hero or heroine notices or how he/she reacts may not be at all the way you

would. What he or she fears or longs for might be very different from you.

Develop your character so you undertand his or her motivation.

Heroes

and heroines need to work actively toward solving their own problems. They

can’t be passive, or merely pawns in other people’s schemes. Even if

they start out that way, they had better seize the reins quickly or the

reader will lost patience.

It’s

fine for your hero and heroine to make mistakes, as long as they

don’t act stupid. That drives readers crazy. For example, don’t have

them simply not call the police in a crisis without a good reason.

Don’t

overlook the crucial role of past hurts. Build character arcs, let

them grow and change. And interweave that with the plot. Sometimes, it’s

best to save vital pieces of their background for key moments, when they can

reveal these to their love interest—and face the truth about themselves.

Don’t

cheat the reader of those heartfelt hero-heroine encounters—not only of

the sexual variety, either. Even if a scene is painful for you to write, it

may be important to the unfolding character arc.

Also

avoid cliché’s in plotting. Example: Don’t start a book with a lengthy

dream sequence just to build phony suspense.

Start

your book in the right place. The first

chapter should mark the beginning of the main action. In a romance, it’s

often where the hero and heroine meet, or sometimes it sets up their meeting

in chapter two.

Do

not use Chapter One as a data dump in which you fill in all the hero and

heroine’s background. Tell the reader what she needs to know now, and save

the rest of the exposition for when the reader needs or wants to hear

it.

Be

especially wary of flashbacks, scenes that actually put the reader

into a previous scene so that we experience it in real time. These tend to

stop the action and sometimes confuse the reader as to what the story’s

really about.

Some

novels are written as extended flashbacks—The Notebook comes to

mind—but they’re really using a frame, in which the beginning and

ending just showcase the “real” story in the past. This technique is

tricky to use; employ it at your own risk.

Remember,

the reader wants to get caught up in the story. It’s you, the author, who

wants to fill her in on the backstory.

Also,

don’t slip exposition into dialogue where it doesn’t feel natural.

Don’t have characters tell each other what they already know. Put the

necessary background information in your viewpoint character’s thoughts.

Don’t

let your plot ramble. Think about how one

scene leads to another, how your chapter is shaped, and how you build to

turning points. This is called Scene and Sequel and there are entire books

about it.

In

every scene, something should change. Even

if it’s just the hero or heroine’s thinking.

Don’t

write scenes that just take up time or provide back story.

Romance

tip: An editor once said that romance is

not about dating. Avoid restaurant scenes unless something major happens

that needed to happen in that restaurant.

Avoid

convenient-for-the-author syndrome. This is where an author has a

character do things or fail to do things in a way that defies logic, simply

because it suits the plot. You know, there’s a serial killer on the loose

but the heroine decides to take a midnight stroll down a dark alley because

she needs the exercise.

Don’t

forget that your book will be read by real people. Some of them will

have expertise or experiences in whatever area you’re writing about.

Consider sensitivities. Don’t throw in painful topics such rape unless

you’re seriously going to deal with it.

That

brings me to research. If you’re going to write about a

subject, learn about it. This includes the hero’s and heroine’s

occupations. Research online, read books, interview people.

In

the upcoming September release of my Safe Harbor Medical series, The

Surprise Triplets, I counted 31 research files in my computer for this

book alone. Among the topics are: legal guardianships in California, child

development for a 7-year-old, embryo adoptions, divorce, family law, what

it’s like to be pregnant with triplets and visiting someone in prison. I

also interviewed a superior court judge so a courtroom scene would sound

authentic.

Once

you start writing, you don’t have to use everything you know, but

the fact that you know it produces texture and increases the chances of

being accurate.

Try

to find friends with expertise who’re willing to review what you write. I

have a friend who’s a nurse and another who’s a private investigator who

review my stuff. They are wonderful people.

“Show,

Don’t Tell” is a vital tool in the

writer’s toolkit. Use perception, dialogue and point-of-view to put the

reader into a scene instead of merely summarizing it. I’m afraid I can’t

go into too much detail here, but I wanted to touch on that.

Part

II: Ongoing Career Choices

If

you decide to self-publish, approach that as a business, in addition

to the business of writing itself. You are now your own publisher. You are

ultimately responsible for the look, editing, content etc. Research what’s

involved. There’s plenty of material on-line, including Smashwords.com’s

guide, Amazon’s info, etc.

Copyright

your self-published books. You can do it online with the copyright

office.

Keep

learning.

This business is changing almost by the month. What works one year doesn’t

work the next.

Even

if you plan to self-publish, consider approaching an agent if your

book may have major sales potential, foreign and movie rights potential,

etc. If more than one editor shows interest, bring in an agent. You might

have an auction!

When

you contact an agent or an editor, act confident. Don’t apologize

for existing or run yourself down.

But

don’t use hype. Editors and agents dislike being told what their

job is. When a query or pitch states that this is a surefire bestseller and

will make their career, it implies that they’re too incompetent to

recognize its merits. Let the work sell itself.

It’s

okay to fail—they won’t put you on some

dark and horrible list to reject forever after just because they didn’t

like your work.

They

will put you on some dark and horrible list if you act

unprofessional. Like sticking a manuscript under the restroom door at a

writing conference. Or perfuming your manuscript and setting off the

agent’s alleries.

If

an agent or editor asks for changes and requests to see the book again, they

mean it. If you agree with the suggestions, revise the book and send

it to the same agent or editor. Can you imagine how frustrating it is

for them to take the time to make suggestions and then see the book end up

with someone else?

Don’t sign with just anybody who claims to be an agent. Look up agents online. Study what they've posted and what others say about them.

Never

sign a contract—including one with an agent--without getting feedback or

legal advice. Look online for sample agent and publisher contracts. There

are too many for me to list here. I believe the Authors Guild has one.

Even

if you have an agent, read your contract.

Remember

that agents and editors are people too. Each has his or her own personality,

taste, experience, expertise, flaws and preferences.

Communicate.

Let your editor know if you’ll be late for a deadline. Tell your agent if

you’re unhappy about something. On the other hand, don’t take up his or

her time with frequent complaints. Be selective.

If

you have a serious concern with an agent, talk to her about what’s

missing. If you can’t resolve it and you think she’s harming your

career, such as through inaction or disorganization, don’t delay in

breaking it off. But be courteous. On the Internet, you can find blogs

about how to break off with your agent.

Part

IV: Publishing Is a Business

--Learn

about taxes. Get a good accountant unless you are one.

--Keep

good records.

--Invest

in your career. This doesn’t necessarily mean spending a fortune. It

does mean joining groups like this Romance Writers of America, taking

classes and attending seminars.

--Look

professional. Don’t go to a conference in ragged jeans and flip-flops.

Will it keep you from selling? It might in these days when we’re all

expected to promote our own work.

--Don’t

flame people on the internet. The Internet is forever and people can be

vengeful. So can their friends.

--Don’t

argue with a negative review. Let it go.

--Don’t

be a snitch. Editors do not trust authors who run to them telling tales

about what they heard on a supposedly confidential loop. And when word gets

out among authors, which it does, you’ll be dogmeat. Authors work together

on promotions, anthologies, blurbing each other’s books, etc. If you’re

a snitch, who’ll want to be associated with you? Play nice.

--Also,

be careful about what you share. You don’t have to tell everyone if

you’re having personal problems. Your editor doesn’t need to know about

your health issues unless they affect your deadlines. Sometimes, others will

use such information in ways that are to your disadvantage, so don’t share

more than you need to.

Authors

today must promote their work. But your Number One job is to write a

great book. And rewrite it. Then write another one.

Begin

learning about all aspects of promotion, from websites to author image or

branding, but don’t let it overwhelm you. Take it one step at a time. You

don’t have to do everything at once.

You

can’t ignore technology. Neither can all of us become experts. Ask

yourself—what’s the one thing you most want to master next? Could it be

Twitter or Facebook? Could be setting up a website, newsletter or blog?

Start learning about that one thing.

Back up your work. You can use online storage such as Dropbox.com. Or a flash drive. I use a combination. But back up often. Losing your stuff is heartbreaking.

Social

Media is great but don’t hardsell your

readers. No one wants to read “Buy my book!” over and over. Post

interesting stuff, wherever you may find it.

While

I can’t cover legalities very well, here’s one caution: Don’t

assume just because a photo is posted for sharing or on a free site that

it’s okay to use it. Never use a photo of a person on a book cover or in

an ad without a signed model release. Just because you took the photo or the

photographer gave the okay, you can’t make commercial use of people’s

images without their permission. This is not true in news reporting. But it

is true for books and blogs.

It’s

usually safe to buy from reputable stock photo sites. They should indicate

that they keep signed model releases on file.

Once

you’re eligible, join the Author’s

Guild. They

have lawyers on staff. While they won’t handle your personal legal

problems, they will answer questions that are of interest to other authors

too. And they conduct very helpful phone-in seminars like one recently on

literary estate planning.

On

reaching a certain level of success:

--Don’t

disrespect readers

--Don’t

disrespect aspiring writers

Maya

Angelou said< “I've learned that people will forget what you said,

people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made

them feel.”

Important ending note: Don’t give up on writing unless you really want to.

Funny Fiction

Nobody

can teach you to write comedy if it doesn’t come naturally. But you can

learn to sharpen your wit and, just as important, avoid common missteps.

First, a clarification. I don’t write one-liners for stand-up comics; that’s a different art. I’m a storyteller. My more than 95 published novels range from dark suspense to light-hearted Regencies to laugh-out-loud romantic comedies, which are what I’m drawing on here.

Yes, you need funny quips, but to be effective in fiction, humor should grow out of:

-

Characters who view the world in an offbeat yet believable way

-

Situations that are honestly motivated but get out of hand

-

The author’s and/or character’s voice

-

Surprise coupled with recognition—the unexpected that nevertheless rings true

-

Fresh situations that are engaging and clever.

The premise of Designer Genes, one of my off-the-wall romantic comedies, concerns a mix-up at a sperm bank that sends a blonde L.A. fashionista named Buffy to introduce her daughter to the baby’s unsuspecting father, Carter, a mechanic in Nowhere Junction, Texas. Right away, you can see the possibilities in the pairing of this unlikely couple.

Some of the humor reflects the heroine’s sheltered background:

Buffy had never personally known an auto mechanic, aside from the supervisor at the Mega-Mall Auto Center. She didn’t think he counted. He wore a suit, for one thing, and once when he’d tried to find the hood release on her car, he’d had to call for assistance.

Other times, the humor springs from my hero’s wry outlook. In this case, it involves his father’s dog, Lucas:

Lucas uttered a sound halfway between a snarl and a whine. Carter had never known a dog so quick to hedge its bets between trying to scare people off and begging them not to hurt him.

I also build on the character of the villain, Buffy’s sleazy estranged husband, who’s trying to cheat her out of her fair share of their property. We experience his viewpoint as he awaits Buffy’s return to LA, and receives an unexpected visitor:

The stout, graying woman walking toward him wasn’t Buffy. She was the woman who’d helped him launch his business twenty years ago. She was also the company part-owner he’d cut off six months ago with the same trumped-up plea of poverty that he’d made to his wife.

She was, in other words, his mother.

Humor can be enhanced by the use of toppers. This is a series of lines or situations that build on a theme. Here’s a brief example:

Hunger pangs gnawed at him. On the flight the airline had prepared peanuts in imaginative ways: roasted, stewed, garlic-flavored, braised and mummified. Nevertheless, that had been hours ago.

As you can see, it helps to pay close attention to the characters and how they might react to their situation. The best humor springs from truth, even in one of those bizarre fictional situations that would never happen in real life.

In One Husband Too Many, my heroine, Jana, wishes she could go back six years, before she met the sophisticated rogue she impulsively married, and respond to the online profile of a farmer who sounded like an ideal husband and father. To her astonishment, her heirloom pendant grants the wish...but the "farmer" turns out to be the same rogue, using another name and involved in a shady project. She knows all about him but, in this reality, he has no idea who she is.

As Drake drives to “his” farm, his pickup breaks down. When he looks under the hood, trying to act knowledgeable, Jana is well aware that he’s clueless.

She

couldn’t let him realize she knew he was faking, not until she figured out

his game. Or until she had one foot on the next bus out of here.

She

pointed to a hose dangling deep within the motor. “There’s your problem.

You tore a hose.”

Relief

washed over Drake’s face. “Man, you sure have keen eyes.” He reached

out.

“Don’t

touch it! You’ll—” she began.

He

snatched his hand away and cursed in French, Italian, Spanish, Japanese and

Mandarin.

“Burn

yourself,” Jana finished.

Let’s list a few things that aren’t funny. In fact, they can be painful for the reader:

-

Characters who act stupid or clumsy in ways that the author has manipulated just to try to juice up the humor

-

More than moderate amounts of embarrassment. Embarrassing a character that the reader or viewer identifies with quickly becomes uncomfortable.

-

Cruelty—lines or scenes that belittle people and situations that might really hurt someone. Fat jokes are an example.

-

Overwriting and excess verbiage. Funny writing is tight and pointed, and cuts away fast.

-

Vagueness. Funny writing is on the mark and self-explanatory. If it isn’t funny on first reading, it doesn’t work.

Of course, no two people have the same sense of humor. What sets one person to rolling on the floor laughing may leave another bewildered or annoyed. This leads me to two important points:

-

In humorous fiction, people still need to care about the characters and what happens to them.

-

There’s no substitute for story. Writing a series of goofy situations will wear thin quickly. The story needs real conflict, a series of evolving obstacles, characters who grow and a resolution that’s emotionally satisfying.

I hope these tips will help you sharpen your humor-writing skills. Thanks for reading!

Covers: Points to Remember

As

a reader, you may scan dozens of covers each time you select a book. Some

appeal to you instantly; some put you off. Others are confusing. You wonder,

Why isn’t this obvious to the cover designer?

Then

one day you self-publish a book and have to design, choose or commission a

cover of your own, since rights to the original cover usually remain with

the publisher.

As

your own artistic director, you discover this seemingly simple task is more

complicated than you thought.

Five

tips to get you started:

-

The genre should be immediately apparent to the reader.

-

The image and words should be easy to discern in a very small reproduction.

-

The colors should show up well against a white background.

-

Keep it uncluttered. Don’t try to include every element in the book.

-

Strive for an emotional connection with the reader.

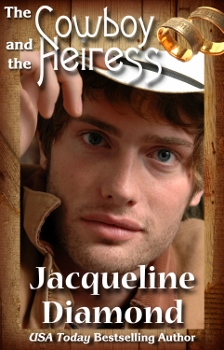

One

reader told me she bought my romantic comedy The

Cowboy and the Heiress

partly because the cowboy on the cover was so cute. I designed

this cover myself using Photoshop Elements and a model whose image I bought for $10 from a stock photo site. I also

used visual elements (a wooden frame and magical wedding rings) from free

sites such as http://www.sxc.hu/

and http://www.rgbstock.com/.

Some

authors are trained artists or have a family member who is. Others may

choose to pay several hundred dollars for a professional cover.

Here

are basic cover-design options:

-

Find and hire a professional designer, if you aren’t one yourself. The results are likely (but not guaranteed) to please you and readers.

-

Buy a cover from a site that will adapt pre-designed covers to your name and title. There are numerous choices, and the look is professional. However, you risk having a cover very similar to other books.

-

Use an aspiring cover designer or other talented semiprofessional. You will pay less, or possibly nothing, and in return provide a credit and exposure. Results vary and you are not necessarily guaranteed exclusivity of design.

-

If you have an artistic eye and are willing to spend the time, learn to use a program such as Photoshop or the simplified version, Photoshop Elements. You can purchase photos of models from a stock site such as DepositPhotos.com, iStockphoto.com, Shutterstock.com and Dreamstime.com. There are various pricing arrangements.

-

Cobble something together with a less sophisticated program and hope for the best. This is risky in today’s competitive ebook market, especially for novels, but it suits some authors.

A word on Photoshop: I don’t recommend trying the professional edition unless you’re a serious graphic designer. Photoshop Elements is more beginner-friendly, but if you have no digital design experience at all (I didn’t), it too can be daunting. If, like me, you would enjoy learning to design covers, it can be fun, but it’s definitely not easy. For starters, I recommend buying a copy of Photoshop Elements: The Missing Manual. This book, which is updated for each new version of the program, provides an overview and a lot of helpful information.

Caution:

if you use a picture of a “real” person, make sure you have a signed

model release or buy it from a stock photo site that keeps these on record.

I recommend against using any image that was simply posted on a sharing

site, as you may infringe copyright.

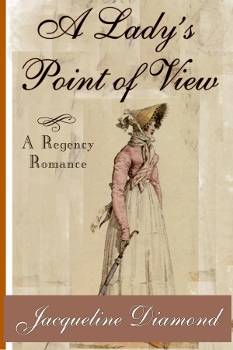

There is no perfect answer for every writer or every book. I’ve used several approaches. My Regency romance covers (Lady in Disguise, A Lady’s Point of View, etc.) were professionally designed by Kelly at customgraphics.etsy.com.

I designed the fun cover for Assignment: Groom! using images purchased from DepositPhotos and Shutterstock.

Hope this helps start you on your journey to ebook cover success!

Self-Editing Your Novel

The

problem with self-editing is that we don’t see our own errors, whether

they’re grammatical or story related. Even the invention of Spell Check,

which ranks right up there with the wheel and dental floss, hasn’t fixed

that problem.

With

the rise of the self-published ebook and print-on-demand, editing one’s

own work has become even more common. There’s no substitute, of course,

for a professional editor, but you can make a lot of improvements on your

own.

Important

note: beta (advance) readers can be extremely helpful. These might be

critique partners, with whom you exchange critiques, or friends who

demonstrate they have a good eye and a strong story sense. Some critique

groups are very helpful too, although watch out for know-it-alls and

put-downs.

I

could write an entire book about self-editing (I actually did write an

ebook about novel writing, shown above), but let’s hit a few highlights.

Areas to look at fall into three basic categories: overall story and

characterization; grammar and spelling; and formatting.

For

the self-published, sites such as Amazon and Smashwords post their own

free formatting instructions that you can download. Most editors and

agents prefer conventional style—double-spaced, indented paragraphs and

no extra line between paragraphs--but more and more accept Internet style,

which means single-spaced with an extra line between paragraphs and no

indentation. Consult their submission guidelines.

Hardly

anyone can fix her own spelling and grammatical errors, unless they’re

simply typos. You really need someone else to do this. However, I

recommend buying a grammar book—Essentials of English, or

something similar—and studying it a page or two at a time. Call it

bathroom reading. It’ll help prevent you from making those errors in the

first place.

Now

for the hardest but most important stuff: revising the overall writing and

shape of the book. Let me share some tips based in part on my years as a

writing instructor.

-

Think like a reader, not an author. Read the first page as if you’d never seen it before. Does it make sense? Do you know where you are, who’s present and whose viewpoint you’re in? Is it off-putting, boring, hitting the action so hard your teeth ache, or filling in tons of background that you don’t yet have a reason to care about?

-

Does the first chapter set up the story? If there’s a prologue, does it have a clear purpose?

-

In the book as a whole, have you included the important scenes? Don’t make the mistake of skipping over the conflict, perhaps because it pushes you out of your comfort zone, and then having the characters reflect later on about what happened.

-

Are the time sequences clear? Are there transitions so the reader can move smoothly from scene to scene and chapter to chapter without getting lost?

-

Have you skipped the boring stuff, such as chitchat (“Nice to meet you”) and unnecessary details about physical actions (“She stepped into the room, walked to the couch, put her hand on the sofa arm and sat down”)?

-

Have you grounded the reader with visual and other physical details, letting the reader see, hear, smell and feel the setting? Have you shown the reader what the characters look like as soon as they appear, or as soon as possible thereafter?

-

Does the narrative have a sense of forward motion? Are you building toward turning points where the action shifts into a higher gear? This is important even in a novel of character, such as women’s fiction.

-

By the end of the first three chapters, have you launched the main action of the book?

-

Are the characters believable? Do they act, think and react like real people? Watch out for characters who are TSTL—too stupid to live—and for Convenient-for-the-Author Syndrome, in which characters do and say things because it suits the plot. For example: If you’re writing a mystery with an amateur crime-solver, don’t have the police simply dismiss evidence for no good reason.

-

Be alert for clichés. While these can be useful shortcuts, too many clog up the story and weaken the writing. On the other hand, avoid metaphors and similes—no matter how clever or original—that are so convoluted or confusing they pull the reader out of the story.

-

Have you done your research? If you deal with medical issues, police matters, government agencies, etc., have you worked to be authentic? After doing as much research as you can, try to find a beta reader who’s knowledgeable in the subject and can catch your mistakes.

-

Do the threads planted in the early chapters pay off later in the book? Have later developments been foreshadowed?

-

Does the climax spring logically from earlier events, even if it’s a surprise? For instance, a mystery reader should be able to go back and find the clues you planted. Don’t just throw in a bunch of suspects and pick one at the end.

-

Does your main character change and grow during the book? This is called a character arc and it's vital to achieving reader satisfaction.

While I’ve just scratched the surface here, I hope these topics will spark your thinking and help your self-analysis, as well as your writing. Good luck!

Eyeglasses of the Regency

See cover photo of A Lady's Point of View

Since people suffered from visual defects in earlier centuries just as they do now, it should be no surprise that, throughout the ages, inventors, artisans, jewelers and glassmakers put their talents to use improving our ability to see.

The earliest known use of lenses to aid vision was in ancient Egypt and Assyria, where people were depicted using magnifying stones such as polished crystals. In the first decade B.C., Roman philosopher Seneca used water-filled objects to magnify text for reading

Around

the year 1000 A.D., Muslim scholar Alhazen

(965-1040)—known as the father of modern optics—wrote a seven-volume

treatise on the subject. In the late 12th century, Marco Polo

claimed that eyeglasses were popular among the wealthy Chinese. The demand

for spectacles grew dramatically by the end of the 15th century,

thanks to the invention of the printing press and the much wider

availability of reading material.

Here

are some good sites about ancient glasses:

https://optical.com/eyeglasses/history-of-eyeglasses/

https://www.antiquespectacles.com/history/ages/through_the_ages.htm

https://io9.com/strange-and-wonderful-moments-in-the-history-of-eyeglas-507302709

My own myopia inspired me, for my sixth traditional Regency romance, to create a nearsighted heroine. In A Lady’s Point of View, Meg Linley--forbidden by her mother to wear eyeglasses--accidentally causes a scandal by cutting Beau Brummell at a ball. Then, sent home in disgrace, she gets into the wrong carriage and is mistaken for a governess.

In 1989, when Harlequin published the novel, I had to dig through books for a few snippets of information on eyeglasses during the Regency. Imagine my delight, when preparing the recent ebook release, at finding a treasure trove of information on the Internet.

Here’s a look at the situation that would have affected my heroine:

An English optician, Edward Scarlett (1677-1743), is credited with developing eyeglasses that rest on the nose and ears. While the exact origin of bifocals is debated, Benjamin Franklin usually gets the credit. Bifocals were found in London after the 1760s.

However, glasses weren’t considered fashionable by the Regency upper crust. Instead, the Beau Monde preferred the quizzing glass, a magnifying lens with a handle that the user peered through.

Quizzing glasses remained popular until the 1830s, when the lorgnette gained in popularity, especially among women. First appearing between 1795 and 1805, the lorgnette is a pair of lenses with a short handle. Also known as opera glasses, these derived their name from the French word lorgner, to ogle.

The quizzing glass was usually set with a magnifying lens, although in some cases a corrective lens was used. Goldsmiths or jewelers provided the frames, often made of gold or sterling silver, with elaborate designs. These hung from a chain attached to the handle—of varying lengths—or loop.

For charming pictures of eyewear from the Regency, I recommend this site:

https://historicalhussies.blogspot.com/2010/08/regency-glasses-and-eyeware.html

Return

to Home Page

Copyright 2013-2022, Jackie Diamond Hyman